By: Martin Grunburg

“She was in the zone!” “He was unconscious!”

When Stephen Curry, point-guard for the Golden State Warriors, three-point-shot maestro and MVP of the NBA’s 2015 season, shattered the league’s playoff three-point shooting record, fans tweeted in unison, “Steph was unconscious!”

Steph has carried that level of peak performance into this season where his team is 36-3. Here are some recent tweets…

This level of peak performance is often referred to as “the zone,” or “flow.” The obvious question, though, is how can we replicate the zone or flow for ourselves — and not just on the basketball court, but anywhere we might need to perform? Recall Shakespeare’s “All the world’s a stage.”

An even better question might be: What core criteria (shared commonalities) are related to such performances?

Well, it turns out that a person’s state of mind (“state”) has a lot to do with their ability to perform at a high level. A “state” refers to a person’s psychology (thoughts and emotions) and even their physiological condition (how they use their organism – their whole body).

For instance, if I’m angry (thoughts and emotions), it would be representative of my psychological state, which is then likely to influence my physiology (body language), which might be represented by clenched fists, tight jaw, furrowed eyebrows, etc. The two – physiology and psychology – are magically interwoven, which means that when you change one you heavily influence the other.

Here’s the best part: We all have the ability to intentionally manipulate our state whenever we desire. And, often the fastest way to do that is simply to address our physiology.

If I stand more erect, pull my shoulders back a little and lift my chin, it’s going to be much more difficult to feel weak, insecure or unhappy. However, if I dwell on being unhappy (psychology), chances are good that my shoulders will slouch and my eyes are likely to gaze down toward the floor (physiology).

Tony Robbins (a world-famous peak-performance coach and strategist), who has coached many of the greatest athletes about this idea of “state” and NLP (Neuro Linguistic Programming), teaches athletes first to recall when they were at a peak state; by creating an anchor, the goal is to create the optimal state “on demand.”

Rather than deviate here about state and anchoring techniques, I highly recommend you check out Tony’s web site and some videos on the topic (or even just his Facebook post on the subject).

An equally essential path to peak performance…

To my knowledge it hasn’t been acknowledged and it’s an essential factor (scientifically speaking) in order to achieve peak performance. In fact, without this component peak performance isn’t possible — it IS the pathway to the ZONE and it’s called habituation.

In scientific terms (psychology), the meaning of this word is incredibly relevant.

Here is Merriam Webster’s definition:

– A decrease in responsiveness upon repeated exposure to a stimulus

Allow that to sink in.

What are the implications of this scientific definition?

First, consider that as a stimulus decreases during a performance, so will a person’s thinking or, to be more accurate, over-thinking and self-awareness. In biological terms, habituation means “the organism learns to stop responding to a stimulus which is no longer biologically relevant.”

“No longer biologically relevant.”

That’s powerful! Any additive information that is identified as irrelevant to the goal at hand (the performance at hand), therefore, will be ignored and discarded (think crowd noise, others’ opinions, etc.), which frees up available energy and attention.

Can you recall the first time you drove a car? How relaxed were you? How would you rate your first driving “performance”? On a scale of 1-10, how would you rate both the performance and the stimuli?

Chances are good that the first time you climbed behind the wheel you were overwhelmed, uncomfortable and even overly critical. High stimulus mixed with being highly self-aware – thinking about a lot of irrelevant information. You may even have been terrified that you might run over someone or get into an accident. You were probably hyper self-aware to the point where driving wasn’t necessarily easy, nor was it much fun. Low performance — zero habituation.

The Three Most Important Traits

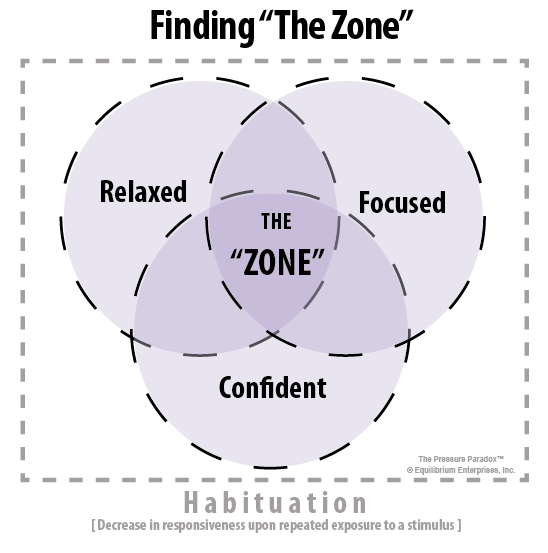

It turns out that habituation fosters what can be considered the three most important and common traits found in any peak performer. Note: While you are likely to identify many more shared traits, none of these three can be missing in any particular peak performance. Each is essential: confidence, relaxation and focus.

When you drive your car you are probably so relaxed and confident that you manage to eat your lunch as you navigate your way to the next appointment. (You of course wouldn’t text on your smartphone or check email, though you’d probably feel relaxed enough to do so.)

In fact, women are so comfortable they might start applying makeup as they fly down the freeway at 65 mph. Not the brightest idea, but the sort of behavior that indicates just how habituated one has become to the driving experience, both the act (performance) and the environment.

Another fantastic byproduct of this habituation (familiarization and implied decrease of external stimuli) is creativity. How many times have you remembered an important task, or had some great insight while you were driving? Or, for that matter, brushing your teeth or showering or shaving? How many creative breakthroughs have you had while you were casually cruising home or to the office in your car?

The connecting link to both the creativity and the creative performance (driving while applying makeup, for instance) is habituation.

Such habituation leads to a heightened state of relaxation, perhaps even entering the realm of the unconscious or subconscious. And, as noted above, that is precisely the point, since one of the key indicators of being in the “zone” is being seemingly “unconscious.”

This may be why a professional comedian or a musical virtuoso might be able to improvise so masterfully halfway through a performance; their habituation carries them to an unconscious, creative state. The same can be said for the greatest athletes and their memorable performances – masterful improvisation to a point where the only explanation anyone can render is, “She was just in the zone.”

While the car analogy is a solid example of habituation that almost everyone can relate to, it doesn’t do a good job demonstrating peak performance because one of the key traits is missing: focus.

So rather than imagine a habituated casual driver whose focus might be elsewhere, let’s now envision a NASCAR driver traveling upwards of 200 mph, and you will quickly see how all three characteristics come into play.

[Much of this is from my latest book, The Pressure Paradox]

BTW: Check out the below video to see the path to habituation and I’ll cover that in the next post. ; )

Comments remained turned off. ; ) To reach me and share your thoughts you can find me (twitter) @thehabitfactor or email me at mg AT thehabitfactor(com)