By Martin Grunburg

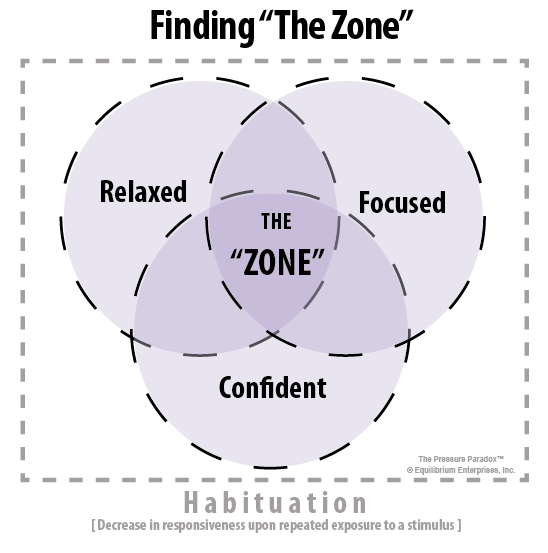

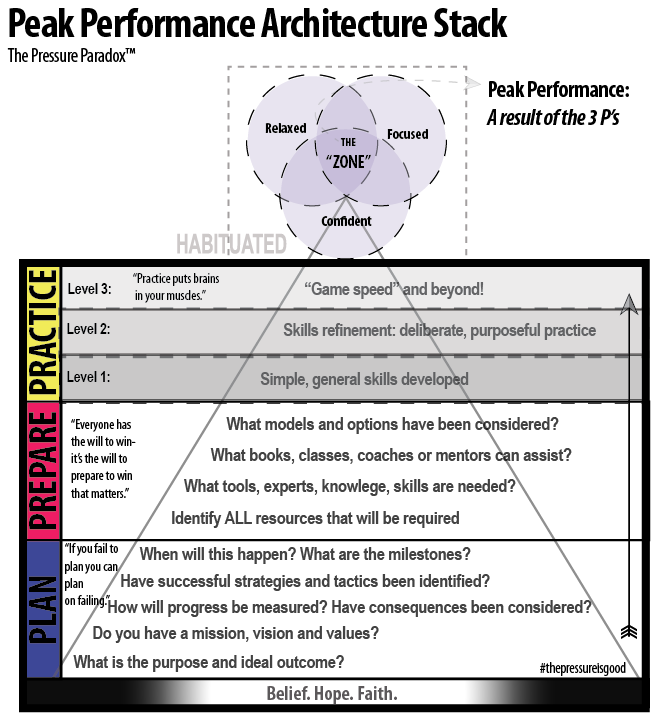

In my last post I shared that becoming habituated to a particular skill or craft is almost always a requirement to experience a peak performance. Whether you’re a stand-up comic, presenting a sales pitch, raising VC funds or playing basketball, becoming habituated first is essential.

It’s important to recall that habituation infers a lack of stimulus to irrelevant information (related to one’s goals/objectives). This is a powerful idea since irrelevant data (lights, cameras, self-awareness, others’ opinions, etc.) tends to diminish the available energy and greatly reduce your ability to focus and concentrate.

Since a key trait of the “ZONE” is focus, this is important to remember. In fact, of all the traits critical to a “zone” experience, focus may be the hardest to call upon. The other two traits are confidence and relaxation (think loose/not tense).

Here’s what a couple all-time-great performers have to say about this idea of habituation.

Michael Phelps simply states that the pool is his “home“— it’s hard to be more habituated than that!

Floyd Mayweather (49-0) put it as succinctly as one can, saying, “I am in my home“… “once I am in the square circle.” (the boxing ring)

That’s habituated. Perhaps two of the most dominant athletes in their sport (in their era) saying/sharing the same insight.

Confident. Check

Relaxed. Check.

Focused. Check.

Even author Malcolm Gladwell (Outliers), who wasn’t directly referring to peak performance or even the “zone,” but was theorizing about “life success,” pointed to the only constant among all his researched “outlier” subjects, and it was something he termed “the 10,000 hour rule.”

Care to guess what happens if you or I do something (anything) for 10,000 hours? That’s correct: We’d develop the corresponding habit and at the same time become habituated to the act or performance.

So, the pathway to the “Zone” and peak performance more often than not demands intentionality and behavior design. Just think about how the military handles new enlistees: They intentionally design their behaviors (habits) to support objectives/goals of the military.

Thus, the crafting of purposeful, supportive habits that align with our goals isn’t just a good idea for goal achievement, it’s a requirement to become a great performer.

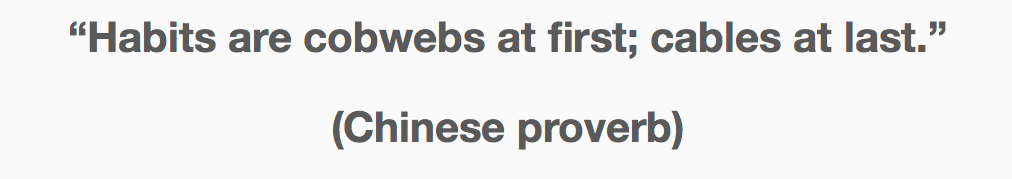

Habits, though, more often than not, are crafted slowly and painfully (at first), until they become comfortable and automatic (at last).

Recall how difficult it was to tie your shoes the first time, and now it’s effortless.

While you’re not likely to have a peak performance tying your shoes, the process of habituation reveals itself as the path to peak performance.

Nobody can become habituated without repeated exposure to a “thing” — an act or a performance. We all collectively marvel at Steph Curry, point guard for the Golden State Warriors (watch the prior post video) and Steph’s shooting skills. Then, notice how much extra time and effort he spends above and beyond his peers.

The exceptional life demands exceptional effort.

So, what does the path to habituation look like?

It’s built upon a foundation of belief, hope and faith, and then deeply layered by what I call “The 3 P’s”: Planning. Preparing. Practicing.

Each of these layers or phases is reviewed in great detail in The Pressure Paradox, and it’s important to just add here that Practice has three layers of its own, based upon the level of pressure: none-light, moderate, strong-excessive. Taking any performer through this architecture stack (which can take years) helps to ensure the likelihood of becoming habituated and, therefore, the likelihood of a peak performance.

Comments remain turned off. ; ) To reach me and share your thoughts, find me on Twitter @thehabitfactor or email me at mg AT thehabitfactor(com)